Stephen Franzoi began his career in psychological research on May 21st 1974 (the day after the guru's wedding to a woman 10 years older) in Kalamazoo, Wisconsin investigating "members of a very curious and popular religious cult" which was not actually as popular as its media profile would suggest. In fact, Franzoi has got the timing slightly skewed. Guru Maharaj Ji (aka Prem Rawat) the divine leader of Divine Light Mission had indeed married on the 20th May 1974 but his mother did not denounce him until April Fools Day, 1975. DLM claimed to have 6 million members but this claim was now a lie as well as a fantasy as the the young guru no longer had any connection to the Indian Divine Light Mission and its administrators had turned against him. The young Rawat no longer had a large number of Indian followers, they accepted his eldest brother as the new bona fide Satguru. Young Rawat had not slipped away from his family to marry but had already exiled them to India and was an "emancipated minor" who had a judge's ruling that he could marry at 16.

Essentials of Psychology I Chapter 1

by Stephen L. Franzoi, Ph.D.

Besides taking psychology courses, I also began conducting psychological studies. One of my more interesting undergraduate studies involved an investigation of the members of a very curious and popular religious cult. Allow me to describe this study by briefly transporting you back in time to the fall of 1974.

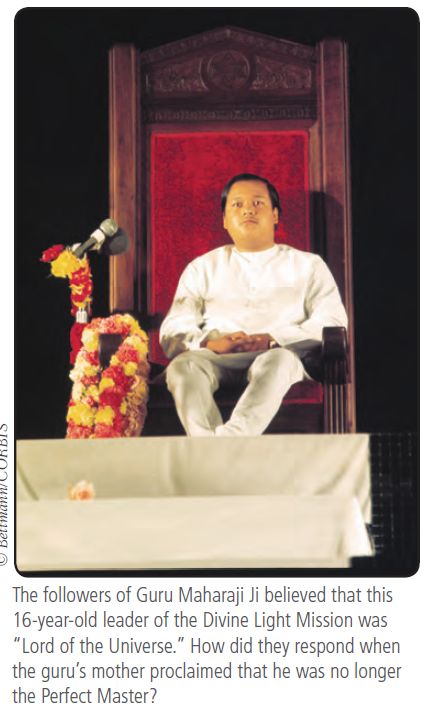

The followers of Guru Maharaji Ji believed that this 16-year-old leader of the Divine Light Mission was "Lord of the Universe." How did they respond when the guru's mother proclaimed that he was no longer the Perfect Master?

The followers of Guru Maharaji Ji believed that this 16-year-old leader of the Divine Light Mission was "Lord of the Universe." How did they respond when the guru's mother proclaimed that he was no longer the Perfect Master?

It was a pleasantly mild Midwest day in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I sat across from Dave, a young and energetic man of 21, in a small, two-story house that was the residence, or ashram, of the local Divine Light Mission. This was a red-letter day for me as an aspiring psychologist, and I wanted to be careful how I asked the question foremost in my mind. The Divine Light Mission was a neo-Hindu religious movement from India that had been receiving much national attention during the past few years. For two months I had visited the ashram, administering personality tests to its members. I was trying to understand why so many people were attracted to this new Eastern religion. Dave had been a devoted member for more than two years, despite the protests of his family. I was a senior in college with aspirations for graduate study in psychology. Now I had the opportunity, with Dave's help, to observe some classic psychological principles in operation.

That year, the Divine Light Mission claimed a worldwide membership of 6 million, with about Maharaj Ji was now more in his thoughts than before; and he was even more certain that the New Age would be dawning soon.

Does Dave's strengthened conviction in the face of troubling evidence to the contrary surprise you? Was his reaction different from what you might expect from a normal person? Was it irrational? Was Dave suffering from some sort of mental illness?

Because I had been exposed to research and theories within psychology, I did not think that Dave's thinking reflected a psychological disorder. Instead, I strongly suspected that his far-fetched rationalizations were more similar to the normal and all-too-ordinary thoughts of someone caught in a very uncomfortable psychological position. Years ago, psychologist Leon Festinger (1957) had outlined a theory to explain how our need to maintain consistency between our beliefs can often lead to irrational behavior. That is, if people hold two thoughts that are inconsistent ("I've paid a high price to follow Guru Maharaj Ji" and "Guru Maharaj Ji is a spiritual fraud"), an internal conflict will be created that people will try to reduce or eliminate. The greater their investment in particular beliefs (for example, "Guru Maharaj Ji is a god and worthy of my devotion"), the more difficult it is for people to reject their beliefs. Known as the theory of cognitive dissonance, Festinger's ideas provided an explanation for how normally rational individuals can engage in some rather odd forms of thought and behavior while trying to justify their past actions. 80,000 located in the United States. The leader of this new religious movement was a 16-year-old boy from India named Guru Maharaj Ji, hailed by his disciples (who were called Premies) as being "Lord of the Universe" and "Divine Incarnation." Premies believed that this young boy was about to usher in the New Age of Peace; and followers were promised salvation if they received the "Knowledge," which was described as being infinite and therefore unexplainable.

Although Guru Maharaj Ji touted himself as a divine entity, he very much enjoyed earthly pleasures such as expensive cars, airplanes, motorcycles, townhouses and mansions staffed with servants, and many Batman comic books and squirt guns as well. What allowed the young guru to live in such luxury were thousands of unpaid Premies, like Dave, who worked at a host of enterprises, including ten Divine Sales thrift stores, a "Cleanliness Is Next To Godliness" janitorial service, and a vegetarian restaurant in New York City. In addition to the income generated by these businesses, all new members' financial assets were routinely funneled into the mission's accounts upon joining, as was any income earned from worldly jobs.

Although Guru Maharaj Ji touted himself as a divine entity, he very much enjoyed earthly pleasures such as expensive cars, airplanes, motorcycles, townhouses and mansions staffed with servants, and many Batman comic books and squirt guns as well. What allowed the young guru to live in such luxury were thousands of unpaid Premies, like Dave, who worked at a host of enterprises, including ten Divine Sales thrift stores, a "Cleanliness Is Next To Godliness" janitorial service, and a vegetarian restaurant in New York City. In addition to the income generated by these businesses, all new members' financial assets were routinely funneled into the mission's accounts upon joining, as was any income earned from worldly jobs.

Which brings me back to why I was sitting across from Dave in the ashram. The previous day, Guru Maharaj Ji had skipped town and eloped with his secretary. Upon learning of this youthful, and decidedly ungodlike, flight of spontaneous passion, his mother had publicly pronounced that Guru Maharaj Ji was no longer the Perfect Master. Instead, she angrily proclaimed that his older brother was the new divine incarnation. Within one day's time, members of the religious movement were being told to believe that Guru Maharaj Ji had gone from being the Perfect Master of their 6-million-member mission to being spiritually "grounded" by his "Holy Mother." How would Dave and the other members of the Kalamazoo ashram make sense of this turn of events? After all, they had paid a high price to gain admission to this religious cult that promised them divine salvation. Yet now the Mission that was their life's work was in danger of crumbling. Had Dave begun questioning the spirituality of his guru and his own commitment to the Divine Light Mission?

Dave's reply was immediate and unwavering. He told me that these recent events were all part of the Perfect Master's plan of ushering in the New Age of Peace. If anything, Dave stated, Guru Maharaj Ji was now more in his thoughts than before; and he was even more certain that the New Age would be dawning soon.

Does Dave's strengthened conviction in the face of troubling evidence to the contrary surprise you? Was his reaction different from what you might expect from a normal person? Was it irrational? Was Dave suffering from some sort of mental illness?

Because I had been exposed to research and theories within psychology, I did not think that Dave's thinking reflected a psychological disorder. Instead, I strongly suspected that his far-fetched rationalizations were more similar to the normal and all-too-ordinary thoughts of someone caught in a very uncomfortable psychological position. Years ago, psychologist Leon Festinger (1957) had outlined a theory to explain how our need to maintain consistency between our beliefs can often lead to irrational behavior. That is, if people hold two thoughts that are inconsistent ("I've paid a high price to follow Guru Maharaj Ji" and "Guru Maharaj Ji is a spiritual fraud"), an internal conflict will be created that people will try to reduce or eliminate. The greater their investment in particular beliefs (for example, "Guru Maharaj Ji is a god and worthy of my devotion"), the more difficult it is for people to reject their beliefs. Known as the theory of cognitive dissonance, Festinger's ideas provided an explanation for how normally rational individuals can engage in some rather odd forms of thought and behavior while trying to justify their past actions.

For me, studying the Divine Light Mission represented one of the miles starts from first of many scientific journeys of discovery that I have undertaken as a psychologist during the past four decades. Many of you reading this textbook will feel a similar intensity of interest in learning about the science of psychology. For others, whose passions burn for different life pursuits, this text, and the course in which it is offered, can still provide valuable knowledge that will serve you well while following other desires.